The collections at the KMMA include a variety of xylophones ranging from one bar to sixteen bars. They can also be differentiated by the type of resonators which can vary from a pit dug in the ground or a rectangular wooden chest to attached calabashes or bamboo branches.

Several scientific studies have already been devoted to the history, origin and distribution of this instrument. That by Olga Boone (1936) is considered to be a pioneering work, along with the studies by C. Sachs, E. von Hornbostel and A. P. Merriam.

On the basis of 108 xylophones, which in 1936 were part of the collections of the then Museum of the Belgian-Congo, O. Boone mapped a distribution area which can be subdivided into two large areas, one in the north (distributed across Cameroon, Central African Republic, Gabon, the north of Zaire and Uganda) and the other in the south (north-eastern Angola, the Kasai-Katanga region in southern Congo, and northern Zambia).

The place of the xylophone in the socio-cultural life of Central Africa must be situated above all in a hierarchic framework. Since it is here generally a complex instrument that requires a great deal of skill in construction technique and in addition is always played in pairs by established and trained musicians, the purchase of such an instrument remains the privilege of people of standing within the community. The local chiefs must certainly be included among them. So we mainly find the madimba in music ensembles associated with and maintained by individuals higher up the social ladder. The music associated with the xylophone is almost entirely connected to the traditional chiefs of a village or a tribe, but the xylophone may also be a part of ensembles that play music during ritualistic ceremonies or to accompany dancing for relaxation.

It is quite clear that an ensemble composed of xylophones, skin drums and slit-drums, together with the ankle rattlers of the dancers and other smaller percussion instruments, can whip up a melody and rhythm.

Learning to play an instrument with so many musical possibilities requires talent and technique. The madimba musicians are held in high esteem amongst their fellow villagers. Tuition on the madimba needs to start early and lessons must begin at a young age. At first, pupils begin by carefully observing established players. Thereafter the teacher explains which accompanying phrases should be played and this phrasal set within the same piece is repeated again and again, forming the rhythmical as well as the tonal basis for the melodic lines of the soloist. When the pupil has gained sufficient knowledge and has perfectly familiarised himself with the various accompaniment motifs, he will possibly be allowed to accompany his teacher at an event. The majority of xylophone players are limited to the role of accompanist and only the most skilled among them may take up the position of soloist.

The simplest of xylophone types is probably the one where a few single loose bars are laid over two bundles of reeds, banana tree stumps or wooden beams and are separated by short thin sticks. This type of instrument consists of a series of loose elements that are always assembled before being played. The space created between the bars and the ground serves as a resonating space. A typical example of this is the pandingbwa from the Zande people of Uele (Congo).

The type of xylophone that logically follows on from the one above is one where the bars are laid across a rectangular wooden chest or box and are attached to it by a thin cord. The manza or bandjanga xylophone comes from the north-western Congo and is played by the Ngbandi and Ngbaka

However, in most cases a calabash is used as a sound box for the xylophone bars, and this is the case for various types that are found in both the northern and southern Congo. To give the calabash a specific timbre, an opening is made in its side into which a cylindrical hollow rod is inserted. On the inside of this is stuck a film that the ntanda nkumbidi spider uses to cover its eggs. This vibrates like a membrane and produces a buzzing sound whenever the bars are struck. The same technique is also applied to certain types of drum.

The difference between the various types of xylophone is also determined by the number of bars.

Less widespread are the didimbadimba, the one-bar xylophone from the Luba (Congo-Katanga) and related tribes. The word didimba simply means ‘bar’ in Kiluba. Surprisingly, although only one bar is played, the instrument is ingeniously put together from one large round calabash with a large opening at the top and two bent ‘arms’ between which the bar is suspended. This instrument belongs very much in the realm of hunters to accompany their own particular songs.

In the same class we should also mention the jimba xylophone with its two bars, which belongs to the same musical and cultural world as the didimbadimba and is played by Tshokwe and Lunda during hunting rituals.

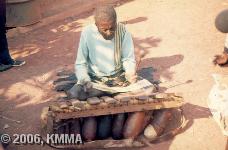

However, the majority of xylophones have more than two bars; generally between 10 and 16. This refers to the madimba (plural of didimba), which is most widespread in the Kasai-Katanga area of the Congo. In the photo’s it is clear how the instrument is built and how the calabashes are attached as sound boxes under the bars. The membrane inserted in each calabash is also clearly visible. The best-known xylophone is from the Pende tribe, and is always played by a pair of musicians in an ensemble or orchestra, similar to other tribes from this region. One of the pair takes on the melody line (generally the ‘soloist’) and the other (the ‘accompanist’) plays the bass accompaniment.

During our field research we noted that the audience ‘understood the melody’: in other words the instrumental melody can be converted into spoken language as is the case with the slit-drum.

This type of instrument is used in recordings of our sound archives made with the Congolese peoples mentioned hereafter where it appears with the following vernacular names:

Anemba (Hamba, Tetela), Bifanda Ntsonge (Yaka), Bifanda Sina (Yaka), Didimba (Luba-Kasai), Didimbadimba (Luba), Djimba (Tshokwe), Dujimba (Lunda), Endara (Nande), Gbengbe (Budja), Kpaningba (Zande), Kpengbe (Ng'bandi), Kpingbi (Benge), Kponingbo (Zande, Zande), Madimba (Bindi, Kete, Kwese, Luba, Luba, Pende, Sala Mpasu, Yaka), Manga (Zande), Manza (Gbandi), Manza (Ngolo, Tanga) (Zande), Marimba (Kanyoka), Midimb (Lunda), Ndara (Ndo), Ndjimba (Tshokwe), Pwandingbwa (Zande), Silimba (Kanyoka, Luba)

Discography:

Bibliography:

© KMMA