Together with the skin-covered drum, the lamellaphone is possibly the most characteristic musical instrument of sub-Saharan Africa. It is known under different names, depending on the region: sanza, likembe, mbira or variations thereof. In English the instrument is sometimes known as the “thumb piano”, a name that was given by the colonials and missionaries and was used when they mentioned this instrument in their writings. Unfortunately this term was not well chosen, since the comparison with a piano is of course not valid. Those who gave it this name were probably guided by the playing technique, whereby the instrument is held with both hands and the iron or reed lamellae are plucked with the thumbs.

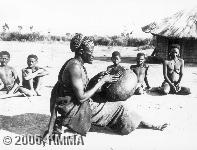

The structure of the instrument with its relatively large number of keys is ideal for the accompaniment of songs performed by the sanza-player himself. Since the majority of types of sanza are quite small, its portability makes it especially suitable for a long journey and it can enliven the monotony of a long march. However, it is also played for the general amusement of the musicians and their listeners, who sit in front of the cabin, and recount day-to-day stories and events that take place in the village. Their role and function in daily life is also one of a purely relaxing nature.

Musically speaking, it is always recurring repetitive patterns of accompaniment that are played on the sanza and one can imagine that on a sanza with three rows of keys (Tshokwe tribe) these patterns are extensive and very melodiously constructed. They are therefore, only played by the more proficient musician. It may come as no surprise that in such examples the tuning of the keys corresponds to the xylophone, but we must add that the mood of the sanza is easy to modify by changing the length of the vibrating end of the keys; they are made longer for lower tones or shorter for higher tones. In addition, research has shown that some compositions for xylophone are also played on the sanza.

It is only logical that an instrument that is so widespread and popular will occur in different forms and types. On the basis of the substantial collection of lamellaphones (695 items) held in the Ethnomusicology Department, the organologist J.S. Laurenty established a classification of the lamellophones found in the Congo. Laurenty identified 18 different types depending on the form of the soundboard, the position of the lamellae and the geographic distribution. The construction of the instrument is based on three main factors: 1) the sound box, 2) the lamellae and 3) the bridge to which the lamellae are attached.

The sound box of the lamellaphone in the Congo varies from a simple rectangular box or a calabash, to a large wooden, hollow, oval sound box.

This last type is typical for the Angba, who are an ethnic group that live in the area of the Aruwimi River and call the instrument lugungu. It consists of a large oval wooden sound box and rests on four small wooden blocks placed on the ground. Given the size of this instrument there has been a tendency to qualify it as an "orchestral-sanza" along with the fact that it only has five keys and as a result is automatically thought of as functioning as a bass. Moreover, with only five notes, no elaborate melodies can be created and one is limited to providing only a bass type accompaniment.

The previous instrument can be compared to the Tshokwe muyemba lamellaphone from the Congo and Angola, at least with regard to the size of the sound box, which consists of a large bulbous calabash. The soundboard of this lamellophone is made from a board with geometric decorations, typical of Tshokwe woodcarving, where a large number of keys (mostly 17) are divided into three rows. The instrument takes its name, muyemba, from the arrangement of the keys, since uyemba is the name for the traditional hairstyle (wig) of the Tshokwe women, where red earth and palm oil is rubbed into each plaited strand of hair. The keys are tuned in such a way that the first row of keys is tuned an octave higher than the second row, which in its turn is pitched an octave higher than the lowest row, resulting in an range of three octaves. The technical complexity of the instrument leaves us to presume that its playing was reserved for the more talented musicians. A large bulbous calabash is used as a sound box, which produces a full sound due to the size of the cavity. To play the instrument, the musician holds the board in both hands and plays it with both thumbs. The opening of the calabash is actually big enough for both hands.

The kakolondondo are the most widespread type in the same ethnic group. Here too a calabash, although smaller, serves as a sound box and only one row of keys is provided. It is striking that these keys are mostly made from the spokes of a bicycle wheel or an umbrella beaten flat. This can be deduced from the tiny hole pierced into the point of the lamellae. This instrument is very popular with the Tshokwe and a lot of musicians have built up their own repertoire that is intended both for themselves and to give pleasure to their listeners.

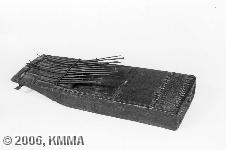

Laurenty named the most common type as the "fluvial" type because it spans such a wide geographical distribution that cannot be attributed to one people or one region. The adjective “fluvial” stands for the distribution of this instrument among the people who live along the banks of the large Congolese rivers. Typical for this instrument is its box-shaped sound box, the iron lamellae and the bridge to which they are attached. The box-shaped sound box originates from a rectangular cube of wood, one side of which is hollowed out to create a cavity. This is then covered with a thin plank of wood which is stuck down with resin or rubber. On the underneath and side of the sound box a hole is made so that the musician can modify the timbre by covering the opening at the bottom with his finger and/or covering the hole at the side by pushing it against his stomach. Generally these lamellaphones have a considerable number of lamellae, anything from 6 to 18, with an average of 10, because this number is generally more practical for the musician to play a bass melody and with which to accompany songs. This model of lamellaphone, generally called a likembe, or a derivative of it, is found more or less to the same degree over a large area of the People’s Republic of Congo, the Democratic Republic of Congo, the south west of the Central African Republic, Rwanda, Burundi and in parts of East Angola and North-West Zambia.

This fluvial type of lamellaphone is present in the Lower-Congo in a rather unusual form where it is abundantly provided with branded and frequently excessive decorations (geometrical drawings, plants, flowers, leaves etc.). This type is certainly unique, which begs the question whether it is a matter of a locally manufactured variant, probably made by one and the same maker, that has by chance become art of our collection. Moreover, previous organological research from this region made no such mention of this type of sanza.

A number of lamellaphones display the singularity of a very exceptional sound box. Most of the sanza have a sound box built from wood or calabash, but in the collection we found seventeen lamellaphones where the sound box was made from tortoiseshell or human and animal skulls. Clearly instruments such as these can be found in the Ubangi region around the large bend in the Congo River in the north that is populated by the Ngombe. Regarding the question as to why human skulls were used, there is no really feasible answer. However inclined one may be to make judgements about the nature of the ritual functions, these interpretations must nevertheless be handled circumspectly. The use of a human or animal’s skull as a sound box for a musical instrument still seems highly unusual.

Something less mysterious but by no means less interesting is the tsimbi lamellaphone, which is found exclusively in the Lower Congo at the mouth of the Congo River and is characterized by the elegant form of the wooden sound box. The traditional rectangular form of the sound box is replaced here with a convex shape that forms a raven’s beak (a term used in organology), which may on the underside be decorated with geometric motifs which in the case of the instrument shown here is involuntarily reminiscent of a type of village map showing the position of the huts and this is in contrast with the purely geometric motifs and decorations that are usually applied to the instruments. Yet here too, no definitive answer can be given concerning the meaning of these motifs.

This type of instrument is used in recordings of our sound archives made with the Congolese peoples mentioned hereafter where it appears with the following vernacular names:

Akasayi (Nande), Alogu ((Wa) Lese, Pygmées), Chisaj (Lunda), Chisanzhi (Kanyoka, Luba, Luba / Lulua, Luba / Songe, Lwena), Chisanzhi Likembe (Luba / Kalebwe), Chisanzhi-chinene (Luba), Dibung (Lunda), Dikembe (Luba, Ndembo), Domo likembe (Ndongo), Dudjimba (Sala Mpasu), Dungba (Pygmées), Dwaza pwa mukuma (Sala Mpasu), Ekebe (Ebonga) (Boyela), Ekembe (Binza, Logbama, Ngando, Zande), Endingiti (Hema), Ensanswa (Batwa), Enzenze (Mongo), Erikembe (Nande), Esanzo (Bampe, Boyela, Ekonda, Ngando, Nkundu), Gbe-kombi (Yogo), Ibeke (Lobala), Ikembe (Ngombe), Ikumu (Leele), Isandji (Bisandji) (Yaka), Isanga (Boyela), Isanzo likembe (Zande), Isen (Mputu), Kadimba (Luba), Kandu (Sala Mpasu), Kasayi (Shi), Katima Likembe ((Wa) Nande), Kiliyo Likembe ((Wa) Nande), Kisanji (Tshokwe), Kisanji ka nsanzu (Luba-Kasai), Kisansi (Kongo, Yaka), Kisanzi (Luba), Kisazhi (Chokwe), Kombi mbira (Yogo), Kundi (Zande), Kyanya (Luba), Lamellofoon (Luba), Libongi (Ngombe), Likembe (Alur, Barombo, Budu, Efe, Gbandi, Luba, Mbole, Mbuti, Mvu, Nyanga, Pende, Shi, Wagenia), Likembi (Ekepeti, Esanza) (Ngbaka-Mono), Lisanzo (Bobwa), Lisanzo likembe (Mombutu), Losokia (Boyela, Saka), Madaku (Zande), Maduku (Azande), Mang'baru Likembe ((Wa) Nande), Muchapata Likembe mbira (Luvale), Nanga ((Wa) Nande), Neikembe (Medje), Nelikembe (Mangbetu), Ngombi (Gbandi, Ng'bandi, Ng'bandi), Omadjundje (Mongo), Omadjunju (Tetela), Sansa (Bena Kosh, Pindi), Sanza (Kongo, Koukouya, Kutu, Lali, Ntandu), Sanzo ababo (Bira), Sanzo apido (Bira), Tshisaasj (Lunda), Tshisaji (Tshokwe), Tshisaji kakolondondo (Tshokwe), Tshisaji lungandu (Tshokwe), Tshisaji mutshapata (Tshokwe), Tshisanji njia nsanzu (Luba), Tshisanji tshia mulundu (Luba), Tshisanji tshia muswaswa (Kanyoka, Luba), Yengo (sanzi, likemba) (Kongo)

Bibliography:

Discography:

© KMMA