In sub-Saharan Africa metal bells are to be found almost everywhere in music ensembles to accompany dancing in the villages. From the early iconographic sources of Cavazzi (1687) and Merolla (1692), two Italian missionaries who left us drawings and descriptions of musical instruments from the Great Congolese Empire, we learn that the single as well as the double metal bell are among the oldest musical instruments known in Central Africa.

Metalworking is held in high esteem in many African communities, so it comes of no surprise that the metal bell is reserved for the chief and secondly for the magician, healer and fortune-teller.

The shape of the bell and the presence or absence of an internal clapper depends mainly on the size of the instrument and its use in each particular society.

Mostly these are smaller metal bells equipped with an internal clapper, sometimes with a simple folded iron leaf or in a miniature version of a western-style bell; probably input arising from the missionaries who built churches everywhere in the Congo. The simplest types comprise a folded double metal leaf with a small metal hook to attach the clapper. In several examples they are attached to the belt or the dancers’ ankles to accentuate the rhythm. However, it is not unusual for bells to be integrated into the musical instrument collections of healers and magicians who use them to chase evil spirits and forces out of the bodies of the sick. Here, a clear parallel can be drawn between the significance of the bell in our society, where it not only functions to summon believers to church or to announce happy or sad occasions by ringing several bells simultaneously, but was also used long ago to prevent evil forces from entering the church. So it should come as no surprise that the small metal bell is always to be found in the world of magical religion and is used, among other things, in ceremonies and rituals linked to twins, or an unusual birth that is laden with doubt and fear. Many tribes perform a ritual at each new moon, one of nature’s most prominent fertility symbols. This is mostly performed by women, with songs tainted by eroticism accompanied by a small metal bell.

In contrast to the smaller versions, the larger examples generally have no internal clapper, but are struck with a beater that sometimes has a rubber ball on it.

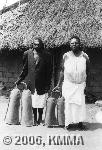

In this category you can also find single as well as double bells. Due to their structure, the latter also have a communicative function because the two sound chambers have a different pitch. Due to the limited range of these instruments, they are generally used in the village or in the chief’s compound; the chief is the owner of the instrument. In early writings, it is mentioned that these metal bells were used in time of war - before, during and after an attack. However, they have also found their place in ensembles that perform the music in the courts of those with highest authority. Connected to the link between the double bell and local power, we can refer to two large double bells called lubemb that are to be found among the Lunda (Katanga, Congo) in the village of Nkalanji where their deceased emperors are buried. These bells are directly linked to the power of the Mwant Yav, the emperor of the Lunda. The Mwadi Muteb (a woman) and the Mukelenge Tshisanda (a man) are responsible for these bells. It’s amazing that they believe so strongly in the magical powers of these objects that they simply keep them outside their hut, as anybody who dared to steal the bells would (according to tradition) die on the spot. This is of course rather unusual in Bantu Africa, with objects that possess such sacred power. Another power that they attribute to these bells is that they will ring independently when the Mwant Yav dies in his residence in Musumba.

In addition to the metal bells in Central Africa, wooden bells are also used in various ways, the most striking being their function in a ritualistic context. The most attractive is the double wooden bell or kunda, cut from one log of wood into the shape of an hourglass that consists of two halves of a bell with two to four thin wooden clappers. The kunda is linked to the nkisi cult (spirit cult), which in its turn involves singing and dancing and the treatment of the sick. In the first instance, it is an instrument of the nganga healer and magical powers are attributed to it. Thanks to the kunda, the spirits can be dominated and influenced by the nganga. This type of bell is connected to a specific spirit and is considered to be its ‘child’. As a consequence this wooden bell is used during ceremonies and dances that are dedicated to the nkisi, to indicate the rhythm simultaneously with the drums and other percussion instruments. It goes without saying that the kunda has acquired an important position as a cult object in Congolese society. However, it has to be said that today, under the influence and impact of western civilisation, which has greatly influenced traditional religions, the bell has all but vanished from the religious sphere there.

In the same Congolese musical culture we find another type of wooden bell: the dibu. The simplest of them are wooden bells shaped similarly to the borassus fruit and have one or two internal wooden clappers. These wooden bells are attached to the neck or even the chest of hunting dogs. It is not uncommon in the Congo to find dogs that do not bark and for this reason a wooden bell is attached to chase the game and to know its whereabouts. The larger and often decorated examples are among the accessories of the nganga are therefore linked to the nkisi cult. They can be distinguished from ordinary wooden bells by a sculpted handle and the geometric decorations that have been applied to the sound chamber.

This type of instrument is used in recordings of our sound archives made with the Congolese peoples mentioned hereafter where it appears with the following vernacular names:

Bozomu (Bali, Ndaka), Elondja (Mongo, Tetela), Elonja (Pygmées), Elonja / Elonza (Mbole), Elonza (Hamba, Ngando), Elonza (Elonja) (Boyela), Elunzia (Kusu), Epam (Mputu), Gong (Kongo), Iyembu (Leele), Kalengele ((Wa) Lese), Lilonga (Ngombe), lley (Mputu), Lokuku (Mongo), Lubemb (Lunda), Lubembo (Luba, Songye), Ludibu (Luba), Lukèlendè (Luba), Madwila (Sala Mpasu), Mayembu (Iyembu) (Leele), Mokembe (Ngombe), Ndje (Lendu), Negbongbo (Mangbetu), Ngezo (Tshokwe), Ngonga (Hamba, Kutu, Ndengese, Pygmées), Ngongi (Mpangu, Mputu), Ngongi (Ngondji) (Kongo), Ngunga (Tetela), Ngunga (Ngonga) (Mongo), Njeke (Mongo), Nkonga (Boyela), Rupwamb (Lunda), Tuzundo (Tshokwe)

Bibliography:

Discography:

© KMMA