Burundi - one of the ancient kingdoms of Central Africa, to the east of Lake Tanganyika - is now a republic of 6,373,002 inhabitants (according to a 2002 estimate) with an approximate surface area of 27,834 km2 and a population density of 228.96 per km2. Its language, Kirundi, is part of the Bantu family of languages and is very similar to Kinyarwanda and Giha, the languages spoken in the ancient neighbouring kingdoms of Rwanda and Buha respectively. Buha is now part of the Republic of Tanzania and Rwanda has become an independent republic.

Apart from Rwanda and Tanzania, Burundi is bordered by the Democratic Republic of Congo. Its orographic relief is dominated by Mount Heha, with an elevation of 2,760 metres. The country's main conurbations are Gitega, Bururi, Rumonge and Ngozi.

Burundi is inhabited by three population groups: the Tutsi, the Hutu and the Twa. The main activities in which these three groups have traditionally been engaged have always been agriculture (millet, sorghum, maize, sweet potatoes, beans, bananas, …) and stock rearing (cattle: the ankole breed of cow; small livestock: goats, sheep, chickens and, more recently, pigs). However, a certain number of trades and secondary production activities are also practised, such as beekeeping, pottery, woodworking, metalworking, basketry and weaving, hunting, jewel-making, etc. Most of these professions are liable to be lost following the introduction of western-made products which are often more practical and effective.

It is generally admitted that the culture of central Burundi (Muramvya, Ngozi and Gitega territories) is representative of the culture of the whole country but major variations are seen in the peripheral territories: the Rusizi plain and the Imbo region in the west, bordering the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC); Buragane and the Moso in the south and south-west respectively, bordering Tanzania. These variations exist in other regions, but are less pronounced than in the four areas mentioned, and are due to the proportions of a particular population group over another and to each group's way of life (agriculture, livestock, pottery or other trade, …).

The cultural aspects associated with the arts in Burundi are numerous, rich and varied. Here, we discuss the artistic field of music and dance.

Every Murundi is a musician at heart, according to Ntahokaja in his article entitled La musique des Barundi (The music of the Barundi), (in: Grands Lacs, 1948-1949, 4-5-6: 45-49). His soul is a taut string which vibrates at the slightest breeze. He sings for all events of life, joyful or sad. The Barundi possess a broad repertoire of songs adapted to all states of mind and all circumstances of life. Joyful songs and sad songs - the latter fewer in number - enhance family and official gatherings, accompany certain rituals and ceremonies and are associated with certain trades. These include the following:

Ntahokaja speaks of uruvyino singing as "mass singing", practised among most of the population. At family celebrations, for example, the singing rises spontaneously from among those present. As the beer glasses are emptied and hearts open, the people are seized by a rousing, lively and cheerful melody. The imvyino style is that of verse and refrain. A (male or female) soloist sings the verses, which are improvisational and have colourful, charming words. The audience, singing in chorus, takes up the refrain - a short, highly rhythmic phrase which is always the same within one song. This song is often accompanied by hand-clapping and possibly also dancing.

The imvyino dance songs may also be categorized depending on the circumstances of their performance.

Private meetings of young girls from the same group of friends, taking the opportunity to

exchange their views on life, their respective family situations and for advice given by

older to younger girls. The songs sung on this occasion are full of advice and elements

critical of society.

Private meetings of young girls from the same group of friends, taking the opportunity to

exchange their views on life, their respective family situations and for advice given by

older to younger girls. The songs sung on this occasion are full of advice and elements

critical of society.

The songs known by this name are sung by a single man or by a small group. Ururirimbo singing is that which best translates calm, subtle feelings. Its themes are prolific and its text is always constructed in poetic form. Ntahokaja observes a resemblance between ururirimbo singing and plainchant: clarity of melody and absence of chromaticism.

Within this category of indirimbo singing, the following classification may be proposed:

Among the types described above, some are accompanied by a musical instrument, whether this be the dance song or the type known as ururirimbo. Some instruments may produce instrumental music, not accompanied by voice, while others may be played in a group or as solo instruments.

The main musical instruments are:

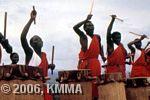

The Burundian drum is made from a piece of tree trunk cut from certain forest species. An adult ox's or cow's skin is stretched over this hollowed-out section of trunk and secured to the wood using wooden pegs. In general, the drum is played with sticks. The drummed rhythms of Burundi differ from those of Rwanda in terms of their rhythms and their more spectacular staging than that of the drums of Rwanda, with a more melodic and generally rigid technique. As in Rwanda, the term ingoma in Burundi has a very wide semantic field; it can refer to percussion drum, ritual drum, dynastic drum, power (royalty or otherwise), reign (or equivalent), government, era, particular country (kingdom). Equally, as in Rwanda, nobody in Burundi could manufacture a drum or have a drum manufactured without a formal order from the king, who alone held the privilege of owning the drums and having them played for himself.

In ancient Burundi, drums were much more than simple musical instruments. As sacred objects,

reserved solely for ritualists, they were only played under exceptional circumstances and

then always for ritual purposes: the major events of the country were heralded by their

beating - coronations, sovereigns' funerals - and, in the joy and fervour of all Burundians,

they kept rhythm with the regular cycle of the seasons which ensured the prosperity of the

herds and fields.

Nowadays, the drum remains an instrument that is both revered and popular, reserved for

national celebrations and distinguished guests. The ancient lineages of drummers have kept

their art alive and, in some cases, have had great success in popularizing it around the world

(L. Ndoricimpa and C. Guillet, Les tambours du Burundi (The drums of Burundi) 1983: 4).

Royal drums: the palladium karyenda drum, which was only brought from its

sanctuary on very rare occasions, particularly during the rites associated with the

umuganuro - celebrating the sowing of the sorghum - and its secondant,

rukinzo. Some of the tasks of the latter are reminiscent of the indamutsa

drum of Rwanda: taking part in the ceremony of the king going to bed and getting up and,

generally, marking out the rhythm of the life of the court; also the fact that it was renewed

with each change of reign. Note that the rukinzo drum accompanied the king

everywhere he went.

Royal drums: the palladium karyenda drum, which was only brought from its

sanctuary on very rare occasions, particularly during the rites associated with the

umuganuro - celebrating the sowing of the sorghum - and its secondant,

rukinzo. Some of the tasks of the latter are reminiscent of the indamutsa

drum of Rwanda: taking part in the ceremony of the king going to bed and getting up and,

generally, marking out the rhythm of the life of the court; also the fact that it was renewed

with each change of reign. Note that the rukinzo drum accompanied the king

everywhere he went.

A tight network of mythical high places formed the political, religious and mythical framework of precolonial Burundi. Among these high places we can include the drum sanctuaries. These were properties owned by the mainly Hutu lineages and they alone, with the king's consent, held the privilege of manufacturing, playing and keeping drums and of bringing a certain number to the court on the occasion of the ritual of the umuganuro. These Abatimbo drummers, "those who hit hard", are probably a remnant of the ancient organization of Hutu principalities before the Tutsi conquest of the country. A sacred drum was enthroned in each sanctuary, surrounded by its attendants, the ingendanyi drums, and a set of drums that played for them.

Four examples of sanctuaries:

For a description of the inanga, look here.

The Burundian zither player produces his piece in a low, whispering voice, so as not to mask the tone of his instrument. Apart from the pieces for the inanga, the instrument can accompany indirimbo songs and imvyino dance songs.

aerophones:

idiophones:

chordophone with bowed string:

* for more information about these instruments, follow the indicated links to the description of these instruments.

© KMMA/Jean Baptiste NKULIKIYINKA